I keep pinching myself, expecting that I’ll soon wake up from this weird and crazy dream. Ten full days have already passed since I arrived in Japan and it still seems surreal that I’m halfway across the world in a country where I can’t communicate much more beyond hello, goodbye, and thank you.

Tokyo skyline from the Metropolitan Government Building.

The last week or so has both felt like an eternity and the blink of an eye. Spending my first six days in Tokyo ended up being fascinating because of its strange similarity to Times Square, but also the shock I received when I was not able to have a meaningful conversation with most people around me. Having spent the last few summers living in big U.S. cities, I had no trouble navigating public transit or other aspects of city life, but the issues came in ordering food (considering both the language barrier and all my dietary restrictions) or even trying to make friends in my hostels. I found myself trying to learn about a culture and country with no way to ask questions, or even just listen and learn.

Yet, even without doing much communicating in my first few days, I was able to see and learn a lot. I spent my first day visiting the famous temples and shrines of Nikko, where I saw the historic appreciation for and representation of Buddhism in Japan. The next day, I was thrown into the opposite environment as I visited the crazy streets of Shibuya, Harajuku, and Omotesandō. These districts are known to be the go-to shopping neighborhoods in Tokyo, and with the shops come large crowds and Japanese pop culture. As I walked down the streets, it was strange to see stores like Zara and Louis Vuitton—reminiscent of 5th Avenue in Manhattan—but still have the street signs and conversations remind me that I was very much away from home.

The third day, however, finally provided some insight for me into Japanese history and culture. I visited the largest collection of Japanese art at the Tokyo National Museum and, mostly due to descriptions being in English, I was able to understand the progression of Japan from the traditional castles and the Tokugawa shogunate to today's bustling cities and skylines.

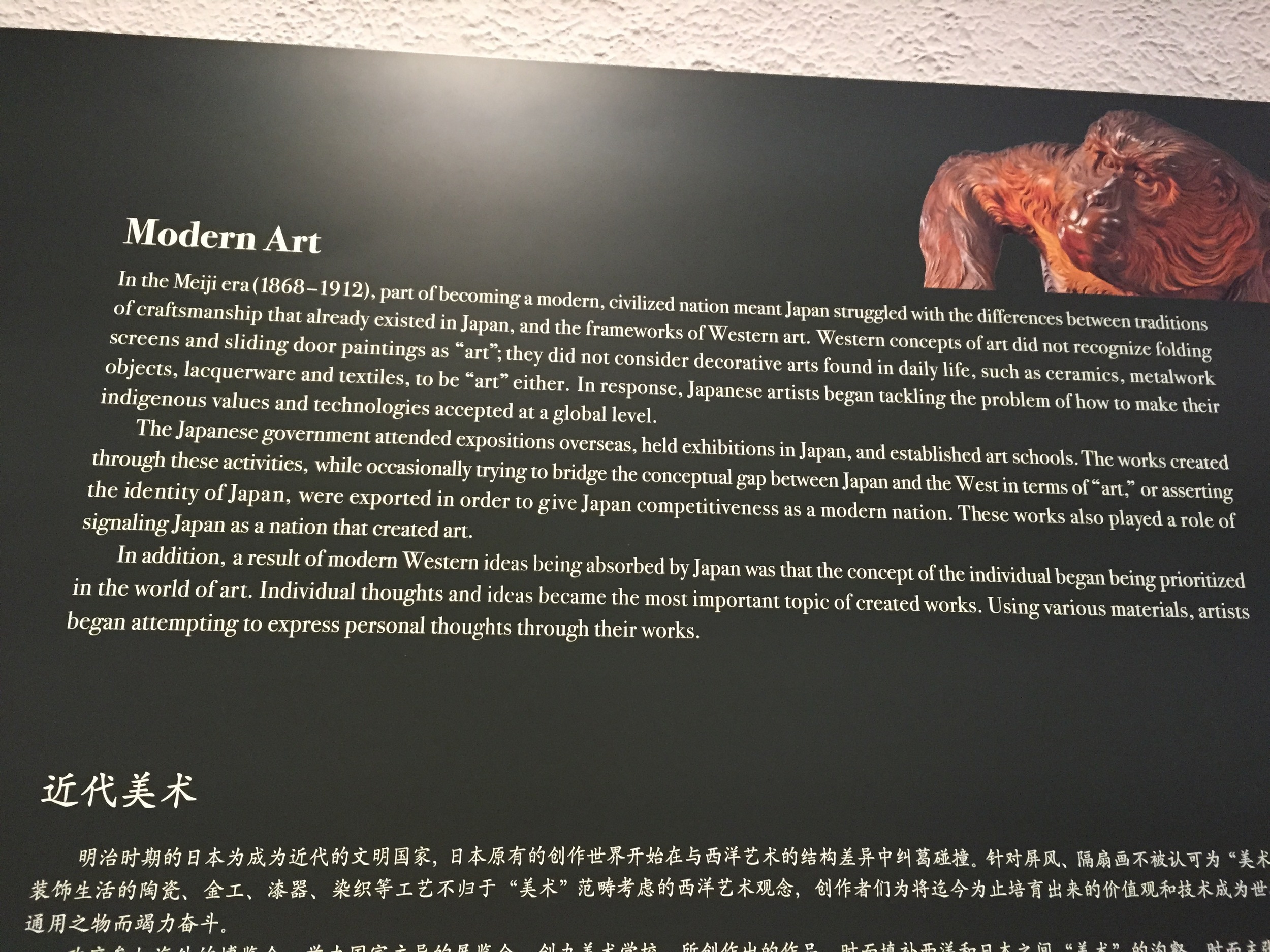

Although the museum started off with more traditional Japanese art, the section that caught my attention was from the Meiji period, which was when Japan shifted from its final stages of feudal society into a more Western form. Although many countries went through some sort of industrialization during the late 1800s to early 1900s, it is interesting to see Japan's somewhat active role in this process.

Many descriptions in the museum (pictured below) discussed how the role of art came into play. Emperors and rulers of Japan realized that the traditional Japanese style was not appealing to the West, and so renowned artists were sent to Europe to study and make their art more appealing. Thus, although Japan was one of the few Eastern countries to avoid colonization in a direct manner, they were still impacted by the pressure to Westernize in order to "keep up" with Europe and the United States. The choice to become Western, then, was actually not one, but just another manner in which a non-white country was deemed lesser or not modern because of its decision to maintain its own customs and traditions.

Nevertheless, Japan has kept much of its original culture, whether it is through its shrines, temples, and practice of Buddhism, or through the almost nonexistence of English throughout the country. They are one of the few non-white countries to be seen as "first world," but have still maintained a strong sense of identity. Although I found this fascinating, it has also been incredibly jarring. Many times while walking through the city streets, I would suddenly stumble upon a small shrine surrounded by skyscrapers. Other times, I would leave some of the most historical temples in Tokyo to be greeted by bright, neon lights and food stalls.

This constant dichotomy between Japan versus the West was strangely, but perhaps unsurprisingly, mimicking my own dichotomy between being abroad as a woman of color and American. As I found myself constantly switching environments, I also had to navigate being one of very few non-white tourists, but still being a tourist. I felt burdened by guilt each time yet another local had to switch to English to speak with me or I could not remember the right words in Japanese or could not produce the correct amount of currency.

Each of these moments have been reminders of my American privilege and how they are going to be critical in traveling to these countries. For, each time I fail to fit in, I will be accommodated because I am American. It is also a stark contrast to the experiences my own parents had in immigrating to the U.S., and the experiences that many American immigrants have, in being shamed to learn and adapt as quickly as they can.

These humbling reminders of my privilege have already made me more critical of my own actions, but also increased my desire to better understand my role as a woman of color in the West, a first generation American, and an individual who wants to create better policies for immigrant communities. Although it is easy for me to remove blame because of my target identities, it is as important, if not more so, for me to accept responsibility for the harm that my agent identities can and will do. It is only through this acceptance that I will be able to learn and move forward, becoming a better ally for many communities, as is my goal throughout this trip.

Type of Japanese art that started to form during the Meiji period. Although still having a clear influence from Japanese scenery, the artistic style, brush strokes, and use of shading is more Western.

These next few days, as I visit Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and their respective memorials and museums, will allow me to continue to reflect on my identity as an American in Japan. Although the process has certainly been difficult so far, I'm looking forward to better understanding my social identities within different contexts, and learning more about Japanese history from the country's own perspective.