Part I: Endings

A couple years ago, I left school for a week to travel to upstate New York for an interfaith conference. The space, an old monastery in the autumn-colored hills of Garrison, was appropriately grandiose for the work we wanted to achieve that week. Brought together by the Nathan Cummings Institute, our goal as community faith organizers and leaders was to find ways to bring together our various religions and ideologies in order to address the changing political and social landscape of the United States.

Although the state of the country over the last year clearly changed in ways we never expected, what sticks with me from that week are the daily faith reflections. Each morning and evening, an individual from a different community shared a key practice; something from their faith that they felt represented a key ideology for them and the community. I particularly recall a lesson from a wiser, quieter man who was one of two representatives of the Indigenous American community. In sharing his beliefs, he talked about the concept of time, but rather how many Indigenous communities viewed it differently from Western culture.

“Time is not linear, but circular. In Indigenous cultures, we don’t believe that something occurs once, never to happen again. Rather, we are moving in circles, passing by moments again and again, building upon previous understandings until the circle is complete.”

Time certainly seems to have stood still in Cuba.

This understanding of the passage of time struck me. It spoke to my anxieties of change, perhaps built up from years of alternating schools and homes and towns. It came back to me again these last few days, as I completed the circle of my Bonderman Fellowship, although I felt in my core that there would be many more circles to come, as there have been many on this trip alone.

Waiting for my final flight back to the United States, I went and picked up a coffee and a lunch in one of dozens of airports I’ve visited over the last year. I listened to echoes of languages distant and familiar, announcements of departures to places I’ve gone and have yet to go, but felt the same butterflies I felt almost nine months ago. Last night, I walked around the dusk-lit streets of Habana Vieja for the last time, feeling the same sense of nostalgia I did during my last night in Ann Arbor, my final night in Michigan, and so many other final nights in homes I’ve made this last year. As I finished this Fellowship, so many asked me, “so, what’re you doing next?” and I felt the frustrating déjà vu of a recent graduate who realized she’d only gotten away from that question for one short year.

My mom asked me yesterday, on my final day abroad, how I was feeling. Was I ready to come back? I told her, although I was excited to see everyone, I couldn’t help feeling sad. “Why,” she asked, “you never know what’s next.”

Leave it to the wisdom of a mother and a world traveler—having made homes and lives in two countries—to remind me that borders are human and there is always something coming in the future.

What’s next?

Part II: Beginnings

Familiarity is a funny thing.

As quickly as new lands became familiar and welcoming, homelands became distant and foreign. Early last week, I boarded a flight from Lima to Fort Lauderdale, one of my four flights in my voyage from Peru to Cuba, and I felt my breath getting quicker, my lungs feeling tighter in my chest, and I knew, for once, it wasn’t the altitude. As scary as other lands had seen from far away, my own USA had become a distant, scary land, and as excited I was to go “home,” I was terrified that I wouldn’t recognize the place I had left a quick and long eight months prior. I didn’t know if I was going home at all.

The problem with your world getting bigger is that everything that it was before seems a lot…smaller.

After spending 287 days out of the last year abroad, I struggle to identify what exactly I am returning to. As I have changed and become a new person over the last year, I know I can’t expect that what I left behind has not changed. I know that these places and things will have continued their cycle of growth and learning, and I just hope that I will be able to fall into the same puzzle when I return. If not, perhaps it is worth remembering that certain things are meant to be outgrown and there are sequels for a reason: sometimes we need to begin again.

Part III: In Betweens

My last day in Cuba was drenched with an unrelenting humidity and a suffocating heat; one that made locals and tourists alike want to crawl out of not only their clothes, but their bodies. We all watched the sky, waiting for the torrential downpour that would save us from the stickiness between limbs that returned after each ice-cold shower.

I alternated between trying to spend as much time outside during my final day in Cuba and hiding in the air-conditioned glory of my apartment room. I reflected on the previous week, a wonderful whirlwind of days and nights wandering through Habana and Cuban countryside with Rasna and Harnek. More so, I recalled how “at home” I had felt, even though I was still thousands of miles away from “home.”

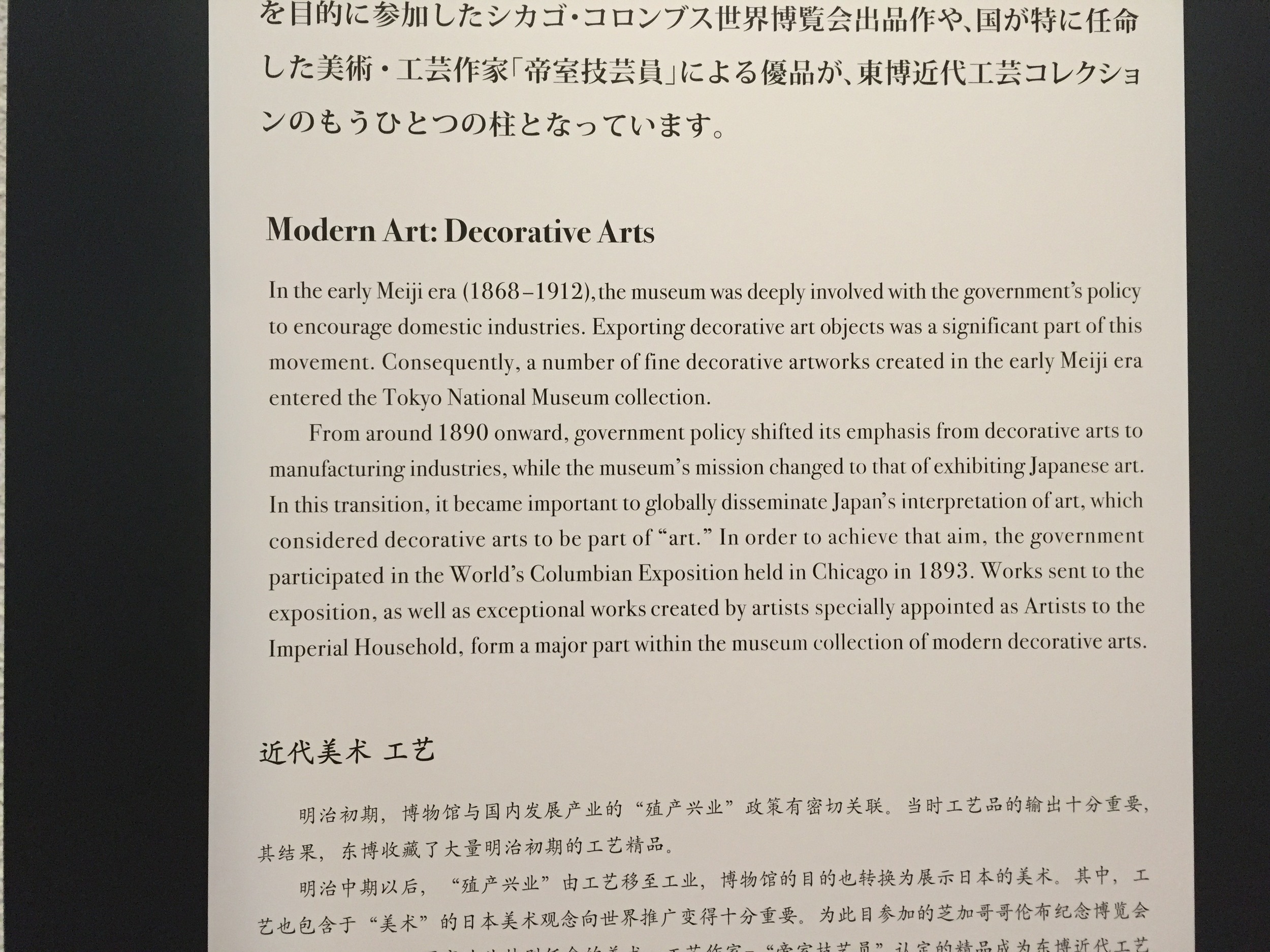

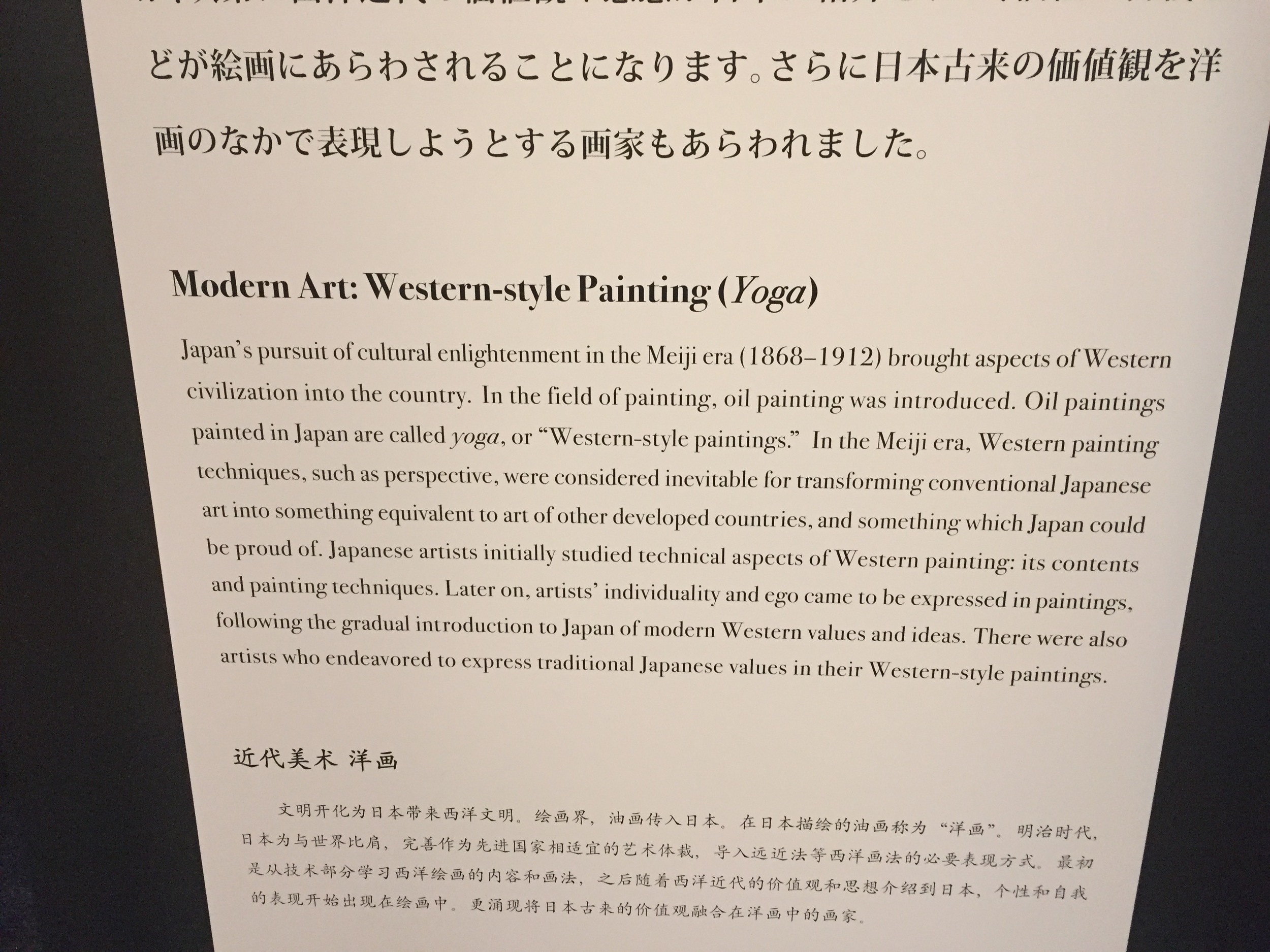

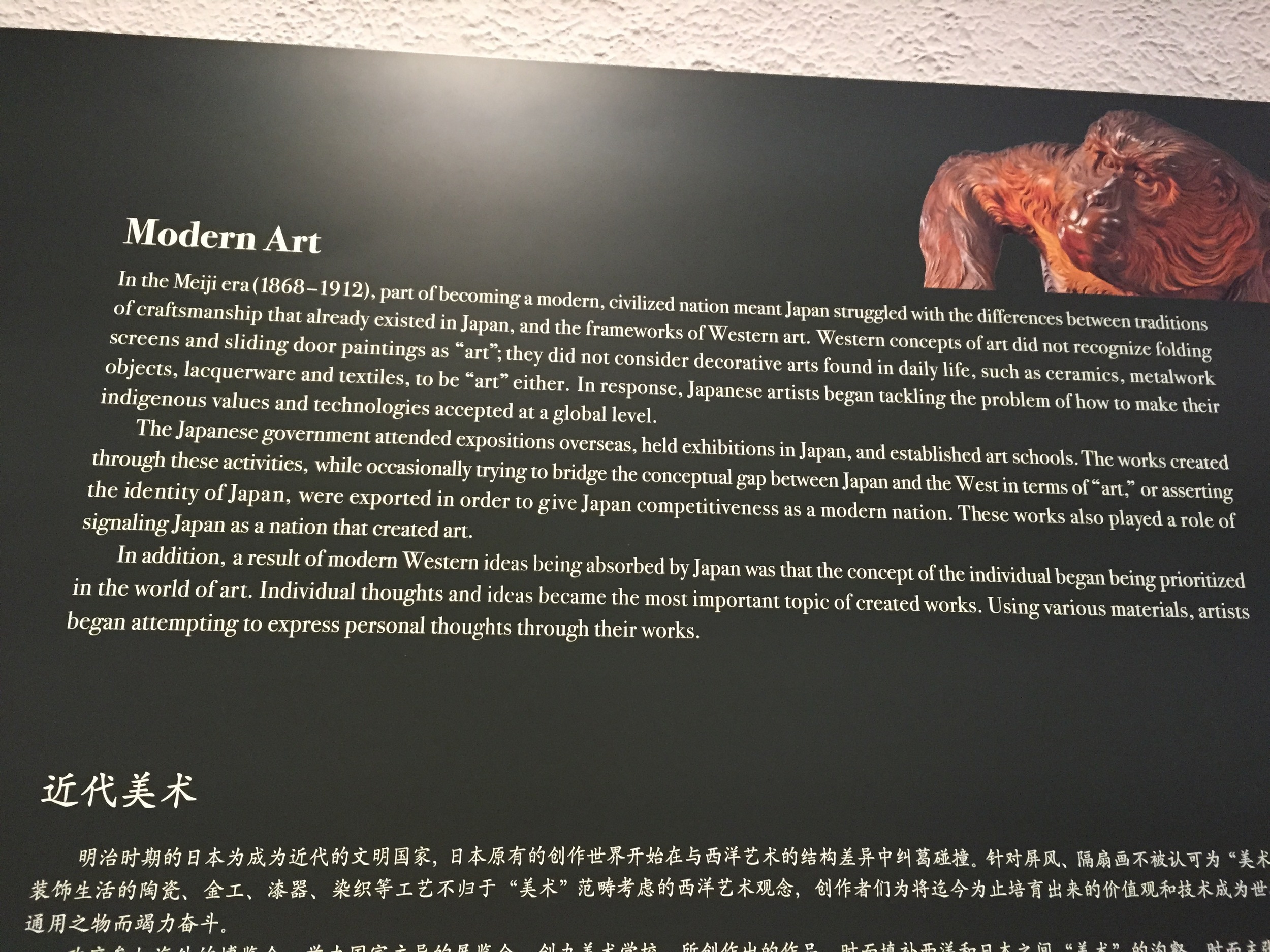

Spending one of our first days in Havana at the Museum of Revolution to learn more about the fascinating history of Cuba.

This last year has made me think…how much do we really need to make our homes? Is it the people or the places or both? And how much responsibility do we each hold in making our places homes for everyone else?

In one hour, I will be getting on my flight back to the United States accompanied by all the butterflies in my stomach. In a lot of ways, I’m back where I was at the LAX Airport, waiting for my flight to Tokyo. I know it will take some time for the dust to settle after I land at my (temporarily) final destination, but I’m thankful for the “eight months of discomfort, growth, change, and finding new homes.” I’m thankful for all the adventure I found and all of it that found me. To all of the people who took me in, showed me kindness and love, and opened their doors and their hearts to allow my head, heart, and spirit to grow.

Although this last year was about un-learning, these next few months will perhaps be dedicated to re-learning. Re-learning what my home was and can be, and that, in fact, my reason for leaving was to learn how to make it better, and that will require sacrifice on many ends. The hardest part of travel is feeling that I have left myself in so many places, and now I’m not sure what parts of me I will be taking back “home.” But I am reminded that the door to these new worlds and families and homes and loves is forever open, it’s simply up to me to step through it.